There’s a coded judgment that people who do well in the mornings hold against those of us who do not. "You’re just not a morning person," they say, the words dripping with the implication that our sluggishness in the AM is a result of slovenliness. It’s the same subtext you see held against fat people, as overweight bodies are viewed as the result of some moral failing. Thankfully, I have in my hand a piece of paper — well, on my computer, a PDF — to refute those biases. I’m not a morning person because I’m lazy, but because it’s coded into my genes.

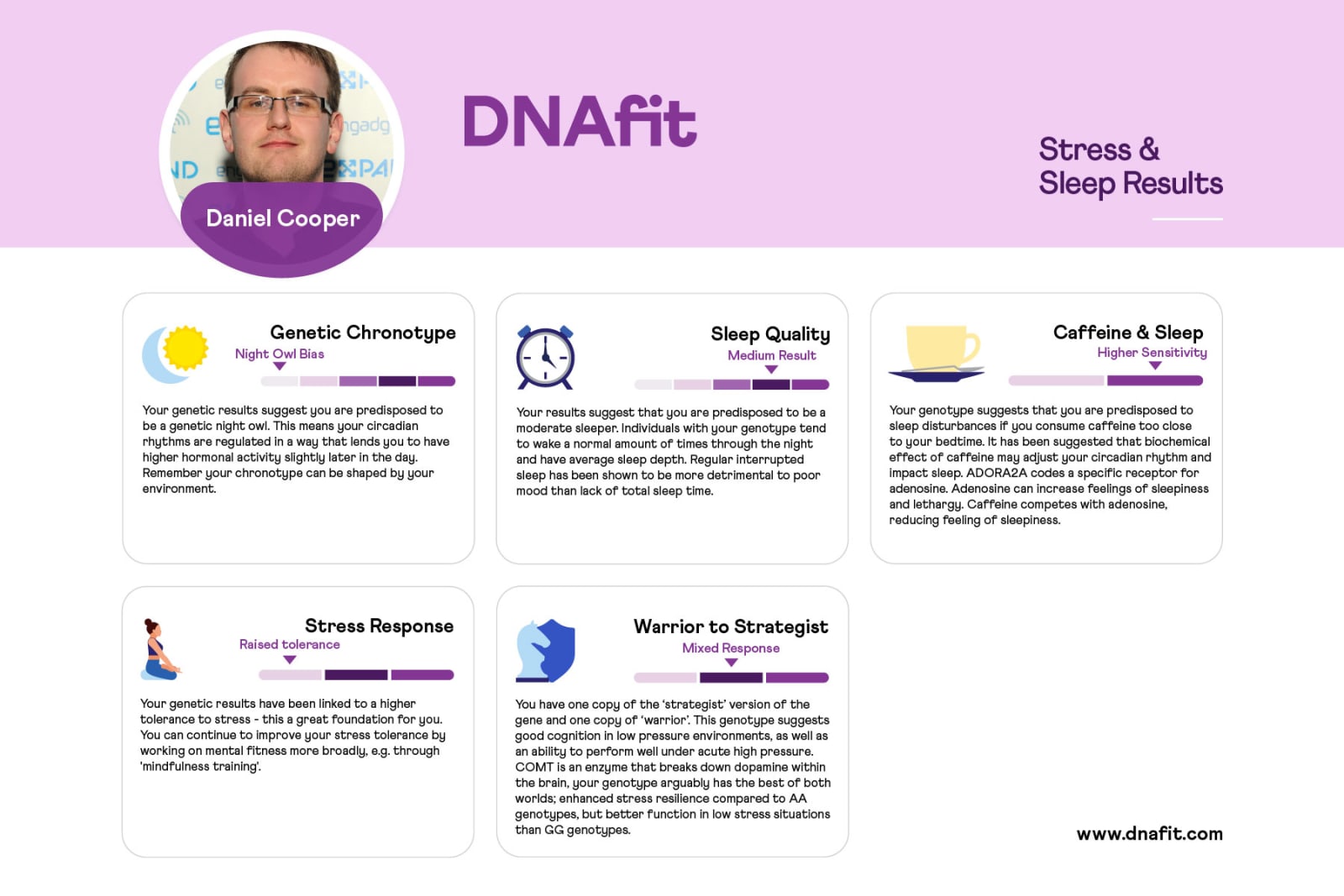

I’ve learned this thanks to DNAfit, a company which knows more about me than I do at this point. It has previously examined my genetics to determine my perfect diet and exercise, as well as peering into my blood to help me get healthy. Now, I’ve tested its latest product, a Sleep and Stress examination to see how I can get calmer in the day and more rest in the night. As before, that required me to take a swab inside my cheeks and send it off to the lab for analysis.

My expectation that, as Engadget’s former "Mr. Chill," (a nickname I have since passed along), my response to stress would be poor. I can’t count the number of panic attacks, heavy breathing and aggressive displacement activity I’ve undergone in the face of a looming deadline. I expected the results to say that my response to stress would make Niles Crane look tough.

"In your case," said DNAfit’s Amy Wells, "you have a higher tolerance to stress than some people." The company’s lead dietician and wellness manager walked me through my results, explaining that I don’t "have a genetic predilection for feeling overwhelmed." In fact, I can take more stress, for longer, without any detriment to my health, than plenty of other people. Who knew.

DNAfit also looks at what the company calls the Warrior / Strategist gene, although it’s more commonly known as Warrior / Worrier. The genotype inside the COMT genes dictates how much dopamine — happy hormone — you release during periods of stress. The more dopamine, the thinking goes, the less clear-headed you are, reducing your ability to plan a clear response.

In an era where our bodies no longer face the threat of, say, wild animals every day, those stresses now come from more mundane sources. Wells suggested that the modern equivalent is when your boss rocks up to you at 4pm on a Friday, demanding you do a job by 5. "Knowing that you haven’t been able to prepare, or comprehend [the task at hand]," said Wells, "means you’ll deal with it less effectively."

DNAfit’s guides offer tips and tricks on how to overcome and manage our genetic responses to stress. In my case, that’s to be mindful, do regular cardio and practice deep and slow breathing so that I’m better prepared for stress. "You need to sit down and comprehend what is going on, then plan your steps to handle the situation." The advice is common for all genetic types, but the extent will vary; very stress-intolerant people should exercise and meditate more than others.

Of course, what was more interesting to me was the examination of my chronotype, the genetic clock lurking inside all of us. Essentially, there’s no ideal sleep pattern that we can, or should, follow and feel smug about. Instead, we should organize our days around what suits us, depending on when we’re going to be the most effective.

The documents told me that I had what’s called a Night Owl bias. "From your genetics," said Wells, "you’re more productive in the afternoon than in the morning." My hormone production spikes later in the day, which explains why I hate mornings so damn much. It also explains why, around 3pm, I get a burst of energy, and my days often finish with more writing than in the morning.

This truth erases years of psychic self-flagellation that strike whenever I think about my failed attempts to become a "morning person." My New Years’ Resolutions in 2001, 2004, 2005, 2006. 2011 and 2012 all saw me resolve to wake up at 6am to exercise. Each year, I managed until January 4th or 5th before conceding that I wasn’t up to the task, and slept in.

"Oh, it’s far better for you to exercise in the evenings," said Wells, "and you’ll have a more effective training session by comparison." That’s not to say that I couldn’t or shouldn’t, have tried to exercise in the morning, but Wells explained that "it’s something you would struggle with, because of your hormonal activity later in the day."

The rest of the test was similarly validating, saying that I’m a poor sleeper with a higher than normal sensitivity to caffeine. I knew that already, and haven’t had tea or coffee regularly in the past six or seven years. That was wise, because my DORA genes are sensitive enough that caffeine will prevent [sleep hormone] adenosine from binding, keeping me awake.

Even when I do sleep, I’m still at risk of rousing thanks to the fact that my genes say that I’ll wake up several times in the night. Wells said that I should try and remove anything from my room that could risk disturbing me, like standby lights or weird noises. That’s easier said than done when you’re sleeping two feet away from a newborn, but it’s still instructive. I had to laugh, though, there are small pieces of blu-tack on every device’s standby light in my bedroom, and every night I sleep with an eye mask and earplugs.

Now, unfortunately, this test isn’t going to be available as a separate test for anyone to take, as with the others. Essentially, the Sleep and Stress tests are only available through a new sequencing process that only works as part of the Health Fit product (currently available for $195 / £145). So, if you want to learn about those issues, you’ll need to go for the company’s flagship test. The company is looking for ways of breaking out the examinations, especially for existing customers, but that will take time.

On one hand, it’s the sort of inessential test that you’d struggle to justify paying for on its own merits anyway. On the other, it doesn’t hurt to have this information if you’re the sort of person already shelling out cash to push your #marginalgoals to the limit. If you’re curious, DNAfit’s recommendations suggest that to be more productive, you should look after your health and balance your day when you know you’re at your best. Pretty much.

In my case, that means working more in the afternoon and less in the morning. Don’t believe me? Shut up, because I’ve got a note from my geneticist.

Source: DNAfit

from Engadget https://engt.co/2IwgRYK

via IFTTT